TMG and the Zone: A Match Made in Heaven

When we first tried out The Massachusetts Game in the thirteenth year of this century, we knew we had stumbled across a gem of a game. The game has a flow to it that smacks of raw, innocent fun.

One aspect, however, that we felt needed to be improved upon was with respect to the dynamic between the pitcher and the batter. We really liked the fact that there were no walks in the game. However, we also realized that even without walks, although there was incentive enough for the pitcher to throw the ball within the reach of the batter, there was really no incentive whatsoever for the batter to swing the bat.

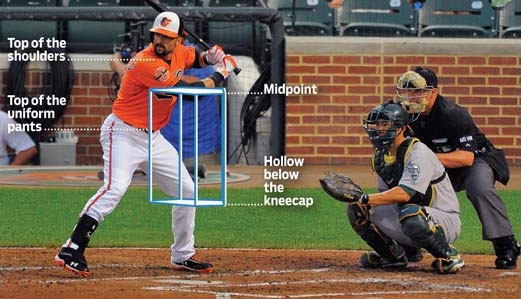

In baseball this is rectified by an imaginary strike zone, defined as “that area over home plate the upper limit of which is a horizontal line at the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants, and the lower level is a line at the hollow beneath the kneecap” and is determined by “the batter’s stance as the batter is prepared to swing at a pitched ball.” If the ball is thrown within that zone, and if the batter does not swing, then a strike is called against the batter.

We realized a similar need for some kind of a “strike zone” such that if the pitcher pitched it into that zone, then the batter was in some way obligated to swing.

We started out by putting a bucket on top of a batting tee behind the batter, and declared, as in cricket, that if the ball hit the bucket, then the batter was called out.

We soon realized that it was in the interest of the catcher to have a zone that one could see through. Hence we constructed a whiffle-ball type zone made of either metal or plastic pipes along with truck netting.

Some argued early on that if the ball hits the zone, then it should only be a strike, and not an out, so as to give the batter the advantage. However, we realized that such a thing would interfere with game play, since the catcher would not have the opportunity to throw out a base stealer on a ball thrown within the zone. But if it is assumed that the batter is out upon the ball hitting the zone just once, then the fact that there is only one out per inning prevents the zone from ever interfering with game play. In other words, if the ball hits the zone, then the batter is out. If the batter is out, then the inning is over. Therefore if the ball hits the zone, then the inning is over. Therefore the zone never interferes with game play.

Moreover, the fact that the batter does not return to the batting point to score makes it possible for a physical zone such as this to even exist in the Massachusetts style of play. This is not the case for baseball, since a physical zone would again get in the way of gameplay, as in the case where a catcher may be trying to tag a base runner out who is attempting to steal home. Such a situation does not even take place in twenty-first century townball, since the home stake is not at the same place as the batting point.

We have heard of at least one baseball entrepreneur, realizing the advantage of a physical zone over an umpire-called zone, trying to incorporate a similar idea into the New York style of play. There really is no way for this to work, however, as this would interfere with game play, both in the case of the ball being pitched into the zone when there is less than one out, as well as in the case where a runner is attempting to score.

It appears that, indeed, the zone and the Massachusetts style of play is a match made in heaven.